Phase One

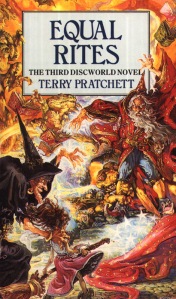

So the chronological Discworld project has been going just over a month, and I’ve read up to Eric, which is the 9th novel. I’m taking a short break for three important reasons: (1) to write up the last few, which I haven’t blogged about yet (one gets behind), (2) to mail order the next batch of books, which I don’t own, and (3) because variety is the spice of life, and I need to read something other that Pratchett for a second (David Shields’s Reality Hunger, if you must know).

I wondered if it would be possible to overdo Pratchett, like cramming one’s face with haribo, at the start of the project. The answer is that whilst the books are varied enough to stay exciting, certain similarities between them which you’d miss with more space between readings are becoming harder for me to ignore. One particularly grating example was that both Wyrd Sisters and Pyramids have dead kings who have to stay around as ghosts in order to watch their sons inherit the kingdom, and aren’t happy about it. Pratchett goes somewhere very different with this character the second time, of course – but it is the second time.

On the other hand, especially with the arrival of the first Watch book, there’s a real feeling of the Discworld taking wing, and I feel that this concern will retreat (or, at least, be replaced with a different one) as early/80s Discworld gives way to “mid”/90s Discworld. It’s still on, basically.